foto mix

CAMERAS OF POLISH CINEMA

The film industry is experiencing a digital camera invasion. Alexa, RED, Sony F3 – these are the names directors of photography give when asked which cameras they use. They are also the responses increasingly being given by Polish DoPs. Yet until recently they would have said the Arriflex 35BL or the Moviecam, while older ones would have recalled the cumbersome Came 300 Reflex, or gone even further back in their memories to the old-timer called the Super Parvo. In any case, they would have talked about analogue cameras recording images on light-sensitive film.

The following article provides a historical overview of the most distinguished cameras used in Polish feature films. We will focus on those cameras using standard cinematographic 35mm film.

At the end of the nineteenth century, Poles were playing an active role in the inventiveness which led to the birth of cinema. These pioneers of cinema included Piotr Lebiedziński, the brothers Jan and Józef Popławski, Bolesław Matuszewski and, above all, Kazimierz Prószyński. Being a pioneer of cinema meant constructing cameras. So we should give the credit for the first film cameras not only to Edison or the Lumière brothers, but also to the Polish precursors of the Tenth Muse - e.g. to Prószyński who invented the Pleograph and the Biopleograph.

But what brought Prószyński fame was his Aeroscope, invented in 1910 - the first camera designed for handheld shooting. The name comes from the camera's unique, pneumatic drive. This drive worked quite loudly, so the Aeroscope served filmmakers, especially documentary filmmakers, only to the end of the era of silent movies. Though it was a period of almost twenty years. Among the filmmakers who used this camera were the English traveller Charles Kearton, and reporters from the fronts of the First World War. There are no examples, however, of this great camera being used in Polish feature film production, although it can't be discounted that they were used.

Here comes the Parvo!

When the American company Panavision launched the noiseless Panaflex camera in 1972, which allowed the recording of audio without the need to place it in sound-proof housing, the so-called blimp, which was full of features to improve filming both with a tripod and by hand, swiftly acquired the nickname of the Rolls-Royce of cinematography. From the most famous cameras from the interwar period, this label would have belonged to the French Parvo camera, which was initially crank-driven and later electric-powered, produced from 1908 by Joseph Debrie's company and then later taken over by his son Andre Debrie.

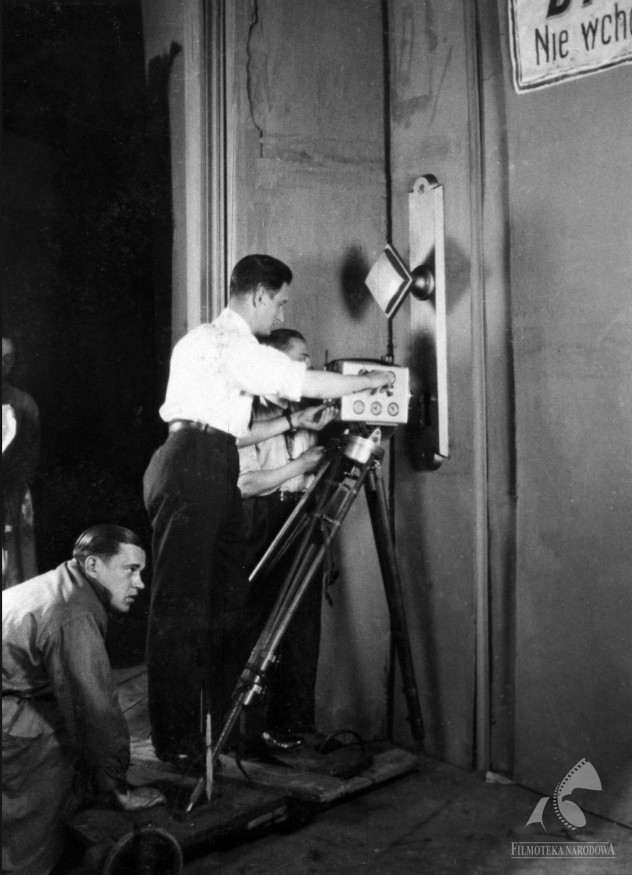

Camera operator Seweryn Steinwurzel with the silent Parvo camera on the set of the film "Kropka nad i"

A characteristic feature of this make of camera, in addition to the precision of the workmanship and the range of modern technical solutions for its time, was its compact design: the output and input magazines for the negatives were not installed on the upper wall of the body, as in most cameras, but they were placed parallel (and not one after the other) and housed in the interior, which reduced the size of the whole object and gave it a neat cubic shape. This was especially true of the L Model, which was extremely popular all around the world.

Parvo cameras were used to film a number of silent movie masterpieces, including "Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens" by Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau and "Bronenosets Potyomkin" by Sergei Eisenstein. They then became a fixture of Polish filmmaking (junior camera operator Stanisław Wohl even had his own "L Model" Parvo), although they were not the only cameras used by Polish directors of photography. For example, Zbigniew Gniazdowski filmed with an earlier model than the Parvo camera - the widely-used French camera, the Pathé, from 1903.

As Edward Zajiček writes in his work "Zarys historii gospodarczej kinematografii polskiej. Kinematografia wolnorynkowa w latach 1896-1939" [An Outline of the Economic History of Polish Cinema. Free Market Cinematography in the Years 1896-1939] vol. I (Łódź 2008), after the breakthrough of sound in cinema, Polish filmmakers had at their disposal four sound-recording studio cameras: three Super Parvo cameras and one Eclair. This last one might have been the Camereclair Radio from 1932, later renamed the Camereclair Studio.

It's therefore clear that, despite the common opinion about the poor technical state of Polish cinema before World War II, it did not differ much from European standards in terms of the cameras. Considerable credit for this goes to the DoPs, especially those who were passionate about modern filming equipment and who went to great lengths to obtain it, such as Seweryn Steinwurzel. Only the modest financial capabilities and the number of film cameras available differentiated Polish film production from the foreign powerhouses.

My kingdom for a camera!

The first years of Polish cinema after the war was a time when the traditions of the interwar period continued, not only in terms of aesthetics (reference is usually made here to such films as "Zakazane piosenki" by Leonard Buczkowski), but also – to some extent – in technical terms. Super Parvo cameras were still used, but they did not meet the needs of the increasing - in intention if not always in practice – film production. The pre-war infrastructure had been destroyed during the war. Everything was missing: including cameras.

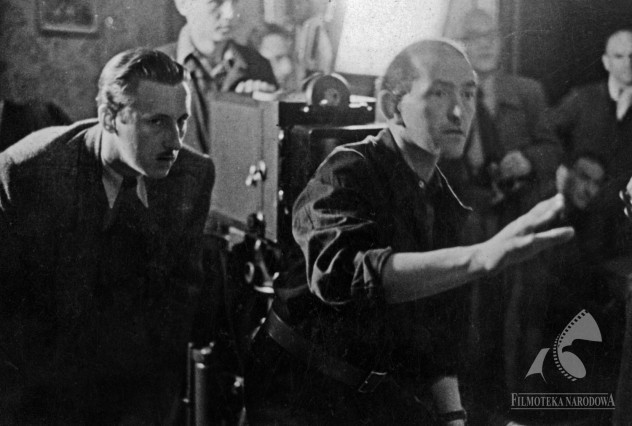

Director of Photography Tadeusz Karwański and camera operator Adolf Forbert in front of a Super Parvo camera on the set of "Zakazane piosenki"

In their book about the Łódź Feature Film Studio, "Fabryka snów" [Factory of Dreams] (Łódź 2013), Stanisław Zawiśliński and Tadeusz Wijata quote the reminiscences of production manager Jerzy Rutowicz: "The first film equipment for the Studio was (...) to a large extent looted from captured Berlin (...).A lot of film equipment was then imported from Mosfilm in Moscow." Operator Witold Sobociński believes, however, that throughout the communist period, Soviet cameras such as the Moskva more often lay in warehouses than were used on film sets.

However, in conquered Berlin, as operator Kurt Weber admits in the same publication, they acquired the excellent Arriflex reporter's cameras – produced by the German company Arnold & Richter AG since 1936.These were the first cameras with a mirror viewfinder, eliminating the parallax error (non-compliance of the image in the viewfinder with the image on the film). Thanks to that and also the slim design which facilitated handheld shots, it was used throughout the world. They initially ended up at the Polish Film Chronicle, although the advantages of the Arriflex were soon discovered by feature film makers - especially those who shot films in harsh outdoor conditions which prevented the use of studio cameras (e.g. "Ostatni dzień lata" by Tadeusz Konwicki and Jan Laskowski as well as "Nóż w wodzie" by Roman Polański).

Until the start of the 1960s, however, Polish feature films mainly used the Czechoslovak Cinephon camera, which was used to film a series of works of the Polish Film School, and to a lesser extent the British Newall camera, although these were modelled on the excellent American Mitchell NC camera, the sound version of which, the Mitchell BNC, dominated the studios of Hollywood and Western Europe from the late 1930s to the early 1970s.

Arri versus Came

It was for "Eroica" by Andrzej Munk, which proved to be one of the masterpieces of the Polish Film School, that the French sound camera the Eclair Came 300 Reflex was first brought to Poland – quite substantial though equipped with a mirror viewfinder, it was quiet and had a number of other advantages. For Jerzy Wójcik, the camera operator on "Eroica", the most important of these were the fish-eye wide-angle lenses: 32mm, 24mm and – which was then a sensation – 18mm.He used them to film the memorable scenes in the camp-based novella with a large depth of focus.

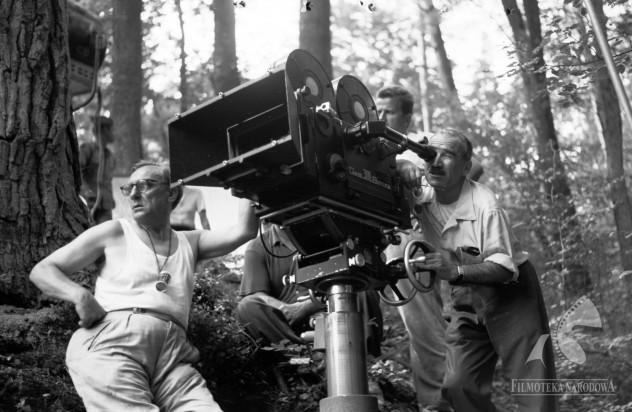

Director Aleksander Ford looks in the viewfinder of the Eclair Came 300 Reflex camera with a wide-screen Dyaliscope lens on the set of the film "Krzyżacy"

In subsequent years, the Came 300 Reflex camera cemented its place in Polish cinema. It was used in the production of such films as "Krzyżacy" by Aleksander Ford, our first feature film shot in Eastmancolor and widescreen format. Another popular piece of equipment was another gem made by Eclair - the relatively small and lightweight (therefore suitable for hand-held shots) Cameflex M3, which was used for example in the outdoor scenes of "Faraon" by Jerzy Kawalerowicz and "Pan Wołodyjowski" by Jerzy Hoffman. This film camera was distinguished on account of its rotating mirror viewfinder, which allowed the operator to carry it while standing on the left or right side of the camera body, putting his left or right eye to the viewfinder.

Meanwhile, in 1964, the excellent Arriflex model – the II C – appeared and for a time in Polish cinema there was a balance between the use of this camera (the blimp allowed filmmakers to shoot sound scenes) and the use of the French cameras. In the Arriflexes, the high-quality American Panavision lenses made their Polish debut on the set of the panoramic "Potop" by Hoffman (1974).The Arnold & Richter and Eclair film cameras came together on the set of "Noce i dnie" by Jerzy Antczak, where the cinema version was made with the Came 300 Reflex and Cameflex cameras and the TV series with Arriflexes. The balance was tipped in favour of the Arriflex II C when filmmakers moved from ateliers into natural interiors which the Came 300 was too big for. But the entire landscape shifted with the arrival on the market (in 1972) of the European counterpart of the Panaflex – the also noiseless and ergonomic Arriflex 35 BL – which soon became basic shooting equipment and would remain so until the end of the 1980s.

The Panaflex, the flagship of the Panavision company, was first used in Poland in 1986 on the set of the Polish-Canadian film "Cudowne dziecko" by Waldemar Dziki. The Came 300 had briefly come back into favour in 1973 in "Sanatorium pod Klepsydrą" by Wojciech Jerzy Has as it lent itself better than the Arriflex to Witold Sobociński's experiments with the widescreen Super 35 system, the format in which the film was shot.

In 1985, in another of Has's panoramic films, "Osobisty pamiętnik grzesznika... przez niego samego spisany" for the only time in Poland a Technovision studio camera was used, which was the same as those used, for example, on the set of "Apocalypse Now" by Francis Ford Coppola.

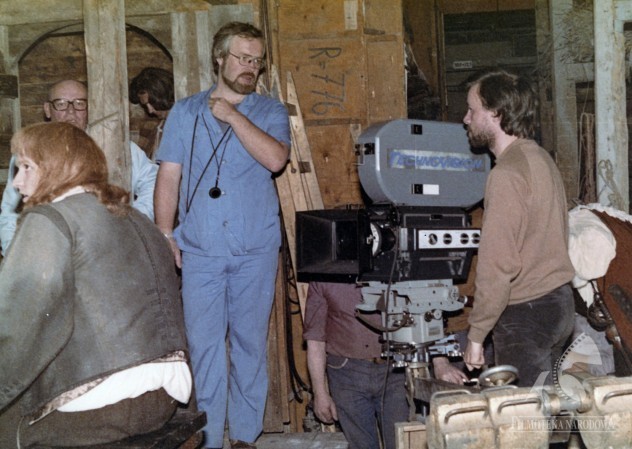

Camera operator Grzegorz Kędzierski with a Technovision widescreen camera on the set of

"Osobisty pamiętnik grzesznika... przez niego samego spisany"

Another modern invention to make it to Poland was the Steadicam which, while not actually a camera, dramatically increased the scope of possibilities and brought a new aesthetic quality to the cinema. At the beginning of the Steadicam's use in Poland, its revolutionary advantages were noticed, for example, by viewers of "Wielki bieg" by Jerzy Domaradzki.

A Stall with Cameras

Before 1989, at least until the arrival of the BL and the Steadicam, the film community complained about the state of the technical base of Polish cinematography, although at the same time they worked wonders to overcome these limits and create outstanding works. There were only isolated examples of films being made with a Panaflex camera or a Moviecam. After 1989, they became commonplace thanks to the return to a free market economy and the greater openness to the West, which meant that in technological terms, our cinema was the equal at least of Western European cinema. Companies specialising in providing film equipment (including Panavision representatives) mean that now a camera operator can order the camera he needs and which fits the budget set by the film's producer. So if he wants to have an Arriflex 435 or 535, or an Arricam (combining the advantages of the Arriflex and the Moviecam) – there are no obstacles. The only issue is the available finances. But operators are increasingly choosing digital cameras – the era of light-sensitive film is being irrevocably consigned to history. And Polish cinema is no exception in this regard.

Andrzej Bukowiecki

In addition to the sources mentioned in the text, I also used the book by H. Mario Raimondo Souto "The Technique of the Motion Picture Camera" (London, New York, 1969) and the Internet Encyclopedia of Cinematography.